White thorns, spinning sky,

White thorns, spinning sky,

each horizontal axis

sings the trinity.

One zenith, then another,

the crowns abide in the air.

Between the towns of Doncaster, Scunthorpe and Goole, less than 10 metres above sea level, 100 square miles of sparsely populated, predominantly agricultural land lie flat to the horizon. The low levels form the northern part of the Isle of Axholme, most of which belongs to North Lincolnshire, with outlying parcels in the East Riding and South Yorkshire. This reclaimed marshland is the setting of White Thorns, a sequence of poems that developed from several walks in 2016 and 2017.

The area is bounded on the east by the Trent, and on the north by the Ouse; at Blacktoft Sands, the confluence of the two rivers forms the Humber. In the 1620s, the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden was commissioned to drain the low-lying land of Hatfield Chase, a process that brought an end to the ‘islanding’ (or flooding) of Axholme, and also transformed much of the surrounding landscape. As part of the drainage project, Vermuyden re-routed the rivers Don and Idle, creating a new channel, the Dutch River, to the north, with a terminus at Goole. The Stainforth and Keadby canal, opened in 1802, links the Don in the west to the Trent in the east; its course through the isle runs parallel to the railway line, just below the villages of Ealand, Crowle and Keadby. A third parallel is provided by the M180, shadowing the railway and canal at a distance of a mile or so, and, with the M18 (linking Doncaster to Goole), effecting a contemporary ‘islanding’ of North Axholme to the south and west.

Since the middle ages, the area has been regarded as a source of fuel, with small-scale peat cutting on Thorne Moors preparing the ground for commercial extraction; by the 1980s, increasingly intensive methods had stripped large areas of the raised peat bog. A colliery – frequently troubled by flooding and faults, and mostly unproductive – also fissured the moors: the pithead was eventually demolished in 2014, and the resurfaced site is now home to a solar park. A few miles south, at Nun Moors, a 22-turbine wind farm stands at the edge of the Humberhead Peatlands National Nature Reserve. Six miles east, near Keadby, rising 90 metres from the flatlands, is a 34-turbine array; the largest onshore wind farm in England. It’s a dynamic illustration of how the exploration and extraction of energy continues to shape this landscape, the wheeling mesh of towers, hubs and blades visible throughout North Axholme, from arable field to depleted mire. It also invites us to consider the expansion of the grid laid down by Vermuyden, its field lines and drainage channels criss-crossed by the remnants of a light railway (serving passengers until 1933, and the peat works until 1963) and, latterly, the buried networks of utility cables and pipes, while, to the south and east, the skies are latticed with power-lines, the net thickening at Keadby, where, between the Warping Drain and the power station, the pylons and turbines seem to meet and interlace, white compasses turning through grey parallels.

Since the middle ages, the area has been regarded as a source of fuel, with small-scale peat cutting on Thorne Moors preparing the ground for commercial extraction; by the 1980s, increasingly intensive methods had stripped large areas of the raised peat bog. A colliery – frequently troubled by flooding and faults, and mostly unproductive – also fissured the moors: the pithead was eventually demolished in 2014, and the resurfaced site is now home to a solar park. A few miles south, at Nun Moors, a 22-turbine wind farm stands at the edge of the Humberhead Peatlands National Nature Reserve. Six miles east, near Keadby, rising 90 metres from the flatlands, is a 34-turbine array; the largest onshore wind farm in England. It’s a dynamic illustration of how the exploration and extraction of energy continues to shape this landscape, the wheeling mesh of towers, hubs and blades visible throughout North Axholme, from arable field to depleted mire. It also invites us to consider the expansion of the grid laid down by Vermuyden, its field lines and drainage channels criss-crossed by the remnants of a light railway (serving passengers until 1933, and the peat works until 1963) and, latterly, the buried networks of utility cables and pipes, while, to the south and east, the skies are latticed with power-lines, the net thickening at Keadby, where, between the Warping Drain and the power station, the pylons and turbines seem to meet and interlace, white compasses turning through grey parallels.

On high, a freehold

of six thousand square metres

threshed by a rotor.

All the feathering threefold

swept into pitch cylinders.

I entered this grid through another: OS Landranger Sheet 112, which I studied before starting out, a new edition, the blank squares filling up with clustered blades. The walks began in Ealand, shortly after dawn on 25 March 2016 (Good Friday), and ended in Thorne around 15 months later, the last of these being an anti-clockwise tour of North Axholme, from dusk until the following afternoon. These weren’t so much linear or circular journeys as transits of a square, or squares within squares, the line (of towpath, track, or minor road) almost always straight, the direction (reset at each corner of the isle) undivided. At certain points in the walks – an intersection of canal and bridge, a chain of pylons making a 90-degree turn – my head would fill with right angles, some imagined, some real, rising out of the flat terrain and my unfamiliarity with the landscape. All this was heightened by walking at night, the senses manufacturing events from scraps of sound (waterfowl in the soak drains, the faint hum of an electric current) and patches of available light (the moon in the water, a signalman’s lamp), and always the filigree of infrastructure, the pylons and turbines compressed to a single plane, the distance collapsed, become abstract, then suddenly present, almost measurable, perception sharpened and distorted by turns, the mind filling in the blanks.

There’s another kind of compression at work in the 68 poems of White Thorns: an isle-wide trek distilled into a series of five-line, thirty-one syllable units, each, perhaps, expanding into its own space, its own plot. There are other passages through this landscape, too, including that of the freight train bearing wood pellets from Louisiana to North Yorkshire (via the Humberhead Peatlands, which sits atop the blackened trunks of a Paleolithic forest, burned by the Romans), and its own story of exhaustion and recovery:

Slow burn, right to left,

twenty-four frames per second.

Twenty-four wagons

of biomass, bound for Drax,

a forest’s offcuts and husks.

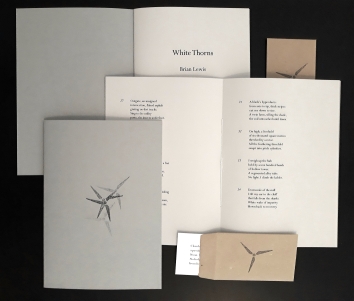

White Thorns is the second pamphlet by Brian Lewis (following East Wind, a sequence of lyrical essays and haiku, which appeared from Gordian Projects in 2015). It is published by Gordian Projects as a hand-stitched pamphlet with hand-stamped covers, and comes with an individual poem, presented in an envelope as an artist’s multiple.

White Thorns is the second pamphlet by Brian Lewis (following East Wind, a sequence of lyrical essays and haiku, which appeared from Gordian Projects in 2015). It is published by Gordian Projects as a hand-stitched pamphlet with hand-stamped covers, and comes with an individual poem, presented in an envelope as an artist’s multiple.

To order White Thorns, please click on the relevant PayPal link below:

UK orders (£5 + £0.90 postage)

![]()

Europe orders (£5 + £2.70 postage)

![]()

Rest of World orders (£5 + £3.30 postage)

![]()

Listen to Brian Lewis read 9 poems from ‘White Thorns’ on location at Keadby Wind Farm, 2 December 2017:

One thought on “On ‘White Thorns’ | Brian Lewis”